Written by James Carlovsky

As a teacher makes decisions about teaching with technology in a classroom, three big questions come to mind:

- Screen time: How much is too much?

- What do standards say about teaching and learning with technology?

- What could be a goal of teaching with technology in a classroom?

Screen time: How much is too much?

As both a parent and an educator, I am concerned about the inundation of screens around children in many contexts. According to a study this decade, the average 8- to 10-year-old spends nearly eight hours a day with a variety of media, and older children and teenagers spend >11 hours per day. Presence of a TV set in a child’s bedroom increases these figures even more, and 71% of children and teenagers report having a TV in their bedroom (Strasburger, Jordan, & Donnerstein, 2010). Young people now spend more time with media than they do in school: it is the leading activity for children and teenagers other than sleeping (Strasburger & Hogan, 2013).

Researchers from San Diego State and Florida State Universities discovered nearly half of teens who got five or more hours of screen time each day had experienced thoughts of suicide or prolonged periods of hopelessness or sadness. That’s nearly double that of teens who spent fewer than an hour in front of a screen (Rossman, 2017).

So what does this mean to the educator? 1) Help educate parents about common technology usage levels at the home. 2) Technology should have a specific and meaningful purpose in the classroom.

What do standards say about teaching and learning with technology?

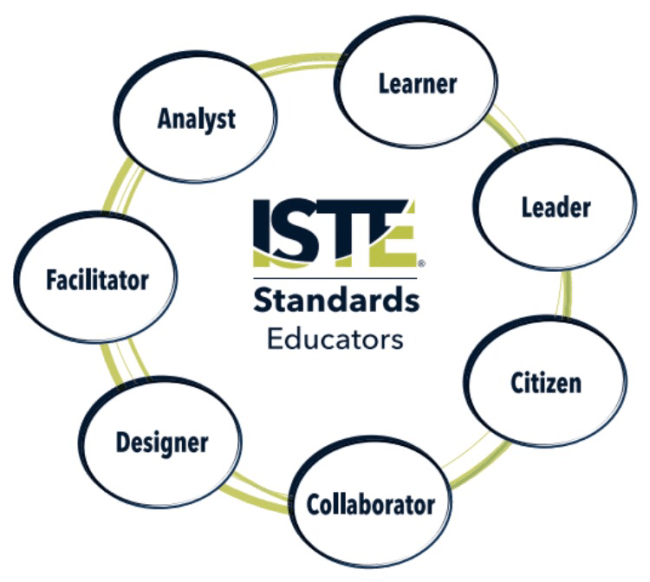

To help answer this question for educators, the International Society for Technology in Education (ISTE) Educator Standards (2017) will be used. An educator is a learner in the classroom as they improve their practice by learning from and with others and exploring proven and promising practices that leverage technology to improve student learning. They are also leaders as they seek out opportunities to support student empowerment and success and to improve teaching and learning.

To help answer this question for educators, the International Society for Technology in Education (ISTE) Educator Standards (2017) will be used. An educator is a learner in the classroom as they improve their practice by learning from and with others and exploring proven and promising practices that leverage technology to improve student learning. They are also leaders as they seek out opportunities to support student empowerment and success and to improve teaching and learning.

Educators inspire students to positively contribute to and responsibly participate in the digital world as citizens. Educators dedicate time to collaborate with both colleagues and students to improve practice, discover and share resources and ideas, and solve problems. Educators design authentic, learner-driven activities and environments that recognize and accommodate learner variability. Educators facilitate learning with technology to support student achievement. Educators analyze and use data to drive their instruction and support students in achieving their learning goals.

A graphic of the ISTE Standards for Students (2016) helps an educator truly understand teaching with technology with the student in mind. Would some of these seven categories even be possible outside the context of teaching with technology? For example, ponder the possibilities of globally collaborating with experts in your subject area. In addition, think about how many ways technology enhances a student’s ability to innovate or design within a classroom. As empowered learners, students can leverage technology to take an active role in choosing, achieving, and demonstrating competency in their learning goals, informed by the learning sciences. This is only a small sample of the power of teaching with technology with student outcomes in mind.

A graphic of the ISTE Standards for Students (2016) helps an educator truly understand teaching with technology with the student in mind. Would some of these seven categories even be possible outside the context of teaching with technology? For example, ponder the possibilities of globally collaborating with experts in your subject area. In addition, think about how many ways technology enhances a student’s ability to innovate or design within a classroom. As empowered learners, students can leverage technology to take an active role in choosing, achieving, and demonstrating competency in their learning goals, informed by the learning sciences. This is only a small sample of the power of teaching with technology with student outcomes in mind.

What could be a goal of teaching with technology in a classroom?

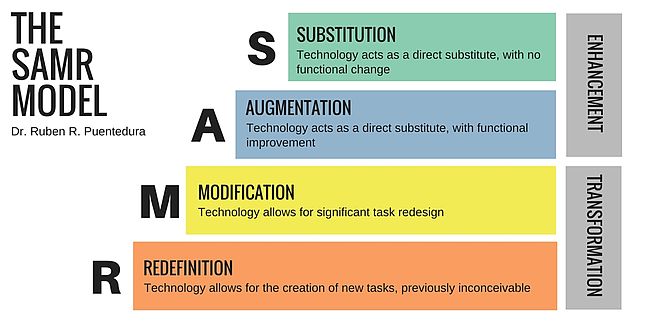

One model commonly used to evaluate technology used in the classroom is the Substitution Augmentation Modification Redefinition (SAMR) Model developed by Ruben Puentedura (2006). Use this model to evaluate whether technology usage, either current or intended, is transformational or merely enhancing what is traditionally done for a particular lesson. The intention of this model is not to say that all substitution is a terrible use of technology nor that redefinition is the only way to teach with technology. Rather, this model can compel a teacher to evaluate a lesson as well as dream about what could be.

One model commonly used to evaluate technology used in the classroom is the Substitution Augmentation Modification Redefinition (SAMR) Model developed by Ruben Puentedura (2006). Use this model to evaluate whether technology usage, either current or intended, is transformational or merely enhancing what is traditionally done for a particular lesson. The intention of this model is not to say that all substitution is a terrible use of technology nor that redefinition is the only way to teach with technology. Rather, this model can compel a teacher to evaluate a lesson as well as dream about what could be.

Some opponents of the SAMR Model argue that the context of the technology matters for integration and this model does not account for context. Other scholars do not like that this model has a limited theoretical background and few peer-reviewed studies showing its validity in a classroom. Some teacher researchers feel this model has too rigid a structure and that the categories should be more fluid. Finally, opponents complain that what really matters in a classroom is the final student process and not the product that takes them there.

Teachers thinking about technology in the classroom need to think about classroom outcomes and pedagogy first. Technology should be learned in the context of those outcomes. Technology has tremendous potential to enhance good teaching and student learning and engagement. A classroom does not need to transform in a day; teachers are probably best served by starting small, but starting in some way. Teachers should notice a relative advantage in using technology to enhance a classroom, being conscious of the screen time of their students. Finally, teachers need continuous professional development.

Specifically, teachers must first understand the relationships between teaching, technology, and learning to promote student growth and achievement. If they understand these relationships, they will be better equipped to access and use technology to support and enhance student learning. (Hamilton, Rosenberg, & Akcaoglu, 2016)

James Carlovsky (’02, MS ED ’10) serves as a professor of mathematics and instructional technology at Martin Luther College.

References

Hamilton, E. R., Rosenberg, J. M., & Akcaoglu, M. (2016). The substitution augmentation modification redefinition (SAMR) model: A critical review and suggestions for its use. TechTrends, 60 (5), 433–441. http://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-016-0091-y

ISTE. (2016). ISTE standards for students. Eugene, OR.

ISTE. (2017). ISTE standards for educators. Eugene, OR: International Society for Technology in Education.

Puentedura, R. R. (2006). Transformation, technology, and education in the state of Maine. Retrieved from http://www.hippasus.com/rrpweblog/archives/2006_11.html

Rossman, S. (2017). Screen time increases teen depression, thoughts of suicide, research suggests. Retrieved from https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation-now/2017/11/17/screen-time-increases-teen-depression-thoughts-suicide-research-suggests/874073001/

Strasburger, V. C., & Hogan, M. J. (2013). Children, adolescents, and the media. Pediatrics, 132(5), 958–961. http://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-2656

Strasburger, V. C., Jordan, A. B., & Donnerstein, E. (2010). Health effects of media on children and adolescents. Pediatrics, 125(4), 755–767. http://doi.org/doi:10.1542/peds.2009-2563