Part 1 – Examining Culture

Written by Benjamin Clemons

This article is part 1 of a 2-part series exploring cultural responsiveness in Christian education. As WELS schools experience growing diversity in their enrollments through either active outreach or demographic shifts, they will need to examine the ways in which culture influences teaching and policy. In part 1 we will begin by looking at culture and its impact.

There is a growing call for culturally responsive teaching practice in public schools (Linton-Howard, 2017; Saphier, 2016). What does this entail, and is it appropriate for WELS schools? I believe that it is beneficial for Lutheran schools to consider the cultures of students and their families in determining teaching practice and school policy. Doing this well requires a careful balance between the necessity for common points of understanding and the biblical encouragement to be all things to all people (1 Cor. 9:10-23).

Throughout its existence, the membership in WELS churches and enrollment in WELS schools has mainly been homogeneous, and we have historically planted new churches in areas that are demographically similar to existing churches. However, changing national demographics are bringing cultural diversity to us. Add to this an overall re-urbanization of the American population, reversing the decades of suburbanization (Glaeser, 2011) and feeding excitement among the younger generation to go to the great cities rather than flee them. The wedding feast of the Lamb as pictured in the book of Revelation features countless guests “from every nation, from all tribes and peoples and languages” (Rev. 7:9). We have the opportunity to welcome those guests to our schools and instruct them in the Word.

Culture and Its Influence

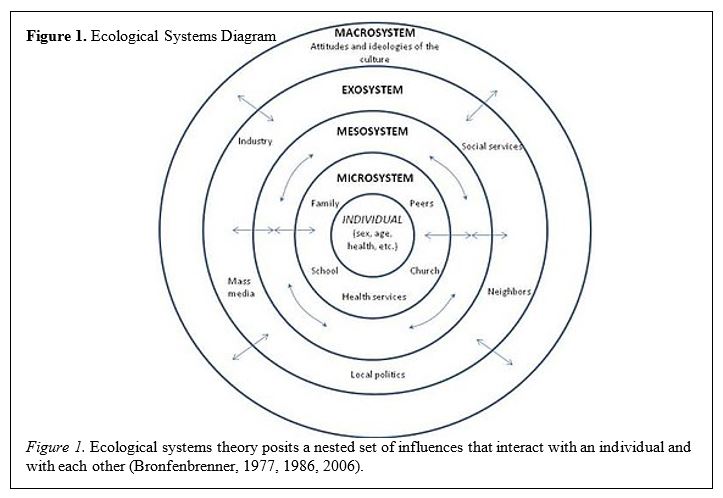

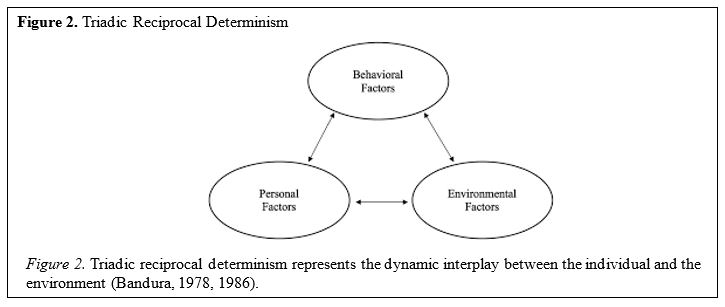

Culture, defined as a set of collective attitudes, beliefs, and understandings that distinguish one group’s members from other groups (Hofstede, 2009), influences behaviors and interactions. Although some aspects of culture—such as cuisine, language, and clothing—are evident on the surface, much of culture consists of attitudes, beliefs, and understandings that are deeply engrained and learned through acculturation rather than explicit instruction. Learning theorists have explained the influence of culture on individuals in many ways and from multiple angles. Ecological systems theory as posited by Bronfenbrenner (1977, 1986, 2006) describes concentric rings of influence around an individual with immediate environments of home, school, and neighborhood holding the most sway, but also acknowledging the interaction between those factors and each other as well as interactions with the larger society (see Figure 1). Albert Bandura (1978, 1986) proposed the concept of triadic reciprocal determinism, wherein the personal characteristics of an individual influence their behaviors and dynamically interact with the environment (see figure 2).

In application to education, constructivists such as Piaget (2003) and von Glasersfeld (1983, 2005) theorized that learning is not just the process of transferring knowledge from one person to another. Rather, individuals construct knowledge based on their previous understandings and experiences, including cultural influences.

Culture Is Manmade

So, where does culture come from? Culture is the human response to the environment and circumstances faced by a given group of people. Over centuries, countless factors shape culture, from the terrain and weather to the types of crops and length of the growing season to the local population density and relationships with neighboring groups. Hofstede (2009, 2011) has proposed six dimensions of culture:

- power distance,

- collectivism vs. individualism,

- uncertainty avoidance,

- femininity vs. masculinity,

- short-term vs. long-term orientation, and

- restraint vs. indulgence.

Each dimension represents a spectrum, and a given culture can fall anywhere on that spectrum. For instance, American culture generally represents a short-term orientation toward the future, while Germany leans much more toward a long-term view. Whether planning for the immediate future or looking years ahead, neither approach is inherently wrong or bad, but focusing exclusively on one or the other could lead to challenges.

The concept of culture can, at times, be challenging for individuals to grasp, especially when their culture aligns with the majority culture of an area. If your culture matches that of where you live, you might not even think about culture, since most people operate on similar understandings or assumptions. However, when you are in a place with a different culture, such as during foreign travel, you will quickly notice differences, from the food to the volume of conversations in public places to what is considered appropriate personal space. The typical response for first-time travelers—I certainly remember thinking this in my first few forays beyond the borders of the USA—is that this is different from the normal way of doing things where I am from and therefore wrong. In reality, the vast majority of the differences—including which side of the road people drive on; eating with forks, hands, or chopsticks; and whether a group is more hierarchical or egalitarian—are all cultural responses usually with deep historical influences.

You Have a Culture

Americans of European descent sometimes view culture as something that other groups (Latinx, African American, Asian American) have. This can be attributed to alignment to the majority culture of the USA (Doob, 2005; Schaefer, 1995). American culture is largely based on Enlightenment ideals brought to the New World during colonization. Although America is a country of immigrants, those early settlers set the tone, heavily influencing the culture of what would become the United States. We see the results today, with a strong European American culture permeating the fabric of our nation from the founding documents, the Protestant work ethic that shaped industrialization, and the highly individualized nature of the American dream (Corbett & Fikkert, 2014).

Relative and Objective Comparisons

Since all cultures grow from human responses to environment and surroundings, all cultures are fallible and fall short of God’s standards of perfection. It may be useful to compare cultures to learn about different attitudes and beliefs, and it may be tempting to compare cultures looking to judge which is better or worse, but we are probably best served by comparing any culture first to God’s objective standards. We will find that no culture, even our own, is perfect, and that all cultures have areas of strength and weakness. We will also see that in many elements of culture, different is not necessarily wrong, as long as that element is not in opposition to God’s Word. You may prefer eating with a fork and spoon, but it is not wrong to eat with chopsticks.

CLICK HERE to read Part 2 . . .

Benjamin Clemons (’03) serves as academic dean and professor of urban ministry at Martin Luther College.

RESOURCES

Bandura, A. (1978). The self system in reciprocal determinism. American Psychologist, 33(4), 344.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1986, 23-28.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1977). Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist, 32(7), 513.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1986). Ecology of the family as a context for human development: Research perspectives. Developmental Psychology, 22(6), 723.

Bronfenbrenner, U., Morris, P. A., Damon, W., & Lerner, R. M. (2006). Handbook of child psychology. The ecology of developmental process. Wiley Publishers.

Corbett, S., & Fikkert, B. (2014). When helping hurts: How to alleviate poverty without hurting the poor . . . and yourself. Moody Publishers.

Doob, C. B. (2005). Race, ethnicity, and the American urban mainstream. Allyn & Bacon.

Glaeser, E. (2011). Triumph of the city. Pan.

Hofstede, G. (2009). Geert Hofstede cultural dimensions.

Hofstede, G. (2011). Dimensionalizing cultures: The Hofstede model in context. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 2(1), 2307-0919.

Linton-Howard, L. (2017). Bright ribbons: Weaving culturally responsive teaching into the elementary classroom. Corwin Press.

Piaget, J. (2003). Part I: Cognitive Development in Children—Piaget Development and Learning. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 40.

Saphier, J. (2016). High expectations teaching: How we persuade students to believe and act on “smart is something you can get.” Corwin Press.

Schaefer, R. T. (1995). Race and ethnicity in the United States. HarperCollins College Publishers.

Sorum, E. A. (1997). Change: Mission & Ministry Across Cultures. WELS Outreach Resources.

Von Glasersfeld, E. (1983). On the concept of interpretation. Poetics, 12(2-3), 207-218.

Von Glasersfeld, E. (2005). Constructivism: Theory. Perspectives and Practice, London: Falmer.