This blog begins a three-article series on the importance of adopting a culturally responsive approach in Lutheran schools. As communities become more diverse, Lutheran schools will want to become more diverse as well. Crossing cultural lines with the gospel can be difficult, as the early church quickly learned (Acts 15). The series is written by Professor Tingting Schwartz, who has personally experienced and intellectually examined these challenges, providing valuable insights to anyone wishing to minister to new people groups.

- What’s in Your Student’s Lunch Box? Focusing on intercultural competence for educators.

- What Language Do the Parents of Your Student Speak? Discussing anti-bias education for young children.

- What Books Are on Your Classroom Bookshelf? Underscoring the importance of the Racial/Cultural Identity Development (R/CID) model for racially, ethnically, culturally (REC) diverse students.

What’s in Your Student’s Lunch Box?

Written by Professor Tingting Schwartz

What Do We See?

One cold, late night in early January, I led my last online workshop, Raising Bilingual Kids at Home. The topic was Biracial and Bicultural Identity Development for Bilingual Kids. Almost all attendees were first-generation Chinese American immigrants who believe raising Chinese and English bilingual children is their family priority.

During the Q & A session, parents had a heated discussion on what they should pack for their children’s lunch boxes when their children go to school. Some parents argued that it was more important to help their children fit in at school; hence, typical American food such as peanut butter sandwiches, string cheese, and Lunchables should be in their children’s lunch boxes. Another group of parents insisted that rice, stir-fries, and jiaozi (Chinese dumplings) are better choices because, as one mother said, “I want my child to be proud of their Chinese heritage.”

Why do we need to talk about immigrant students’ lunch boxes? Trudy Ludwig’s picture book The Invisible Boy might give us a glimpse of these children’s experiences at school. In The Invisible Boy, a Korean American student named Justin brings Bulgogi, a Korean barbecued beef made by his grandma, for lunch. This unfamiliar food immediately gets his classmates’ attention. One of them claims, “There’s No Way I’d eat Booger-gi” when Justin invites his classmates to try it. Thankfully, the invisible boy, Brian, shares a note with Justin telling him that he thinks the Bulgogi looks good.

In 2016, NBC Asian America presented “Lunch Box Moment” to discuss immigrant children’s shared experiences of feeling judged for the ethnic food they brought to school. Many of them reflected on the lunch box moment from their childhood and felt remorseful for rejecting the food their parents made with love because they wanted to fit in.

How Do We Understand the Lunch Box Moment?

The lunch boxes show some aspects of cultural differences. How teachers react to the Lunch Box Moment is vitally important. Their responses will vary based on their intercultural competence, which is defined by Intercultural Development Inventory (IDI Resource Guide, 2021, p. 25) as “the capability to shift cultural perspective and appropriately adapt behavior to cultural differences and commonalities.”

If we want to serve our racially, ethnically, culturally (REC) diverse students well, we want to communicate and act effectively and appropriately across cultural differences.

Dr. Tara Harvey defines “effectively” as achieving what we set out to achieve (2017). For Christian educators, this means sharing the gospel with our students. “Appropriately” means that all involved parties feel respected. For us, this means students feel valued by the teacher and classmates.

Intercultural competence is a learned skill. However, we tend to overestimate our competence when encountering cultural differences. We can use tools like the Intercultural Development Inventory (IDI) to assess our intercultural competence so that we have a more objective understanding of how effective we are when engaging in cultural commonalities and differences.

What Are the Responses to Cultural Differences?

An Analysis of the IDC™

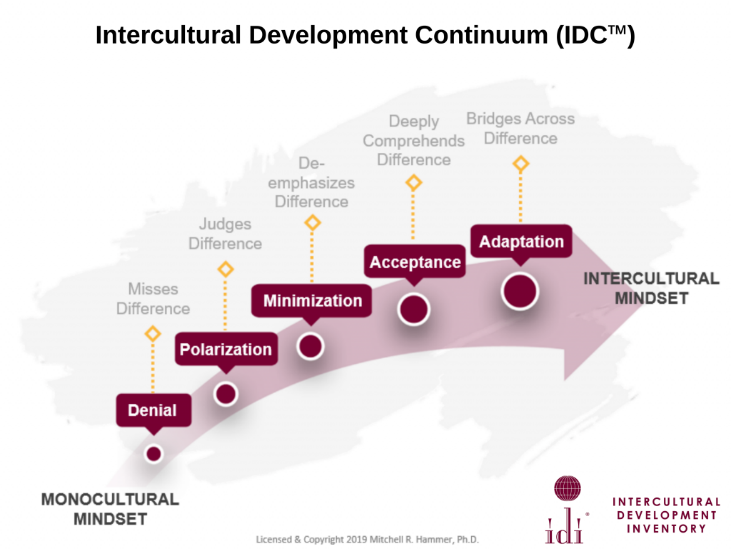

The framework of the Intercultural Development Continuum (IDC™), developed by Dr. Mitchell R. Hammer, theorizes “a set of knowledge/attitude/skill sets or orientations toward cultural difference and commonality that are arrayed along a continuum from the more monocultural mindsets of denial and polarization through the transitional orientation of minimization to the intercultural or global mindsets of acceptance and adaptation.”

The framework of the Intercultural Development Continuum (IDC™), developed by Dr. Mitchell R. Hammer, theorizes “a set of knowledge/attitude/skill sets or orientations toward cultural difference and commonality that are arrayed along a continuum from the more monocultural mindsets of denial and polarization through the transitional orientation of minimization to the intercultural or global mindsets of acceptance and adaptation.”

- The Denial Mindset

IDC describes a denial mindset as a disinterested attitude in other cultures or an active avoidance of cultural difference. When teachers are at the denial stage, they have little recognition of the deep cultural significance of the lunch box moment, thinking, “It’s just food. Why make a big deal of it?” With this type of thought pattern, teachers are oblivious to the lunch box moment, hence failing to address the conflicts between students. From the culturally diverse students’ perspective, it seems that their teachers lack empathy and cultural sensitivity. They may feel that their identities are ignored, and that they are marginalized. Therefore, I’d argue that in the book The Invisible Boy, Brian is not the only invisible student. Justin, the Korean American student, because his identity is ignored, is invisible as well.

- The Polarization Mindset

People could also be at the next stage—polarization. People with a polarization orientation recognize cultural differences but approach them in terms of “us versus them.” Two thought patterns emerge at this stage: either a defensive mindset that says, “My culture is better than yours” or a reversed mindset saying, “My culture is worse than yours.” When people deal with cultural differences using their own culture as the standard to judge other cultures, it is called ethnocentric monoculturalism.

Students or teachers with a polarization mindset might think or say, “That food has a funny name” or “We (the school) should help our students adapt to American food.” When REC diverse students interact with people of this mindset, they might either internalize this message—white culture is better than my ethnic culture—or fight against it. When their lunch is being judged or mocked, REC diverse students could experience forced assimilation at the school cafeteria. For example, in her article “Public Schools, Private Foods: Mexicano Memories of Culture and Conflict in American School Cafeterias,” Salazar (2007) remarked, “Mexicano and other ethnic minority youth confront both institutional and peer pressures to adopt the dominant food norms of American school lunch.”

For diverse students, lunchtime is not just about eating food. It’s a social time. Where they sit and what they eat become matters of fitting in. Diverse students might give up their home lunch and seek to adopt the food habits of the white middle class that dominates American school culture. Or they might sit at a table with students of their ethnicity, where their REC identities do not stand out. This cafeteria table, where diverse students find belonging, then becomes a symbol of psychological safety. As a result, educators often see segregation among white students and diverse students at the school cafeteria.

- The Minimization Mindset

People of a minimization orientation highlight commonalities, such as basic needs and universal values, because of their limited cultural self-understanding. They acknowledge that cultural differences exist, yet believe they are not nearly as significant as the commonalities we share as human beings. People may say, “Bulgogi or grilled steak—they’re both foods. We’re all human beings, and we all like to eat food.” This statement demonstrates a shallow recognition of cultural differences, such as the cultural values behind the food.

People who possess a minimization mindset may not recognize that they themselves have their own ethnic culture. They may worry about focusing on the cultural differences, which would single out people from other cultures. Educators may miss the lunch box moment or deal with it without cultural sensitivity since they find cultural differences of little importance. Minority students might feel that their ethnic identities are ignored or diminished if they hear this type of statement.

- The Acceptance Mindset

At the final two stages (acceptance and adaptation), people hold an intercultural or global mindset. People at the acceptance phase recognize cultural differences and appreciate them. They recognize the food that diverse students bring to school has a rich culture. They might appreciate the food by tasting or asking questions with genuine cultural curiosity. While curious and interested in cultural differences, individuals with an acceptance mindset are not fully able to appropriately adapt to cultural differences and feel challenged to make ethical or moral decisions across cultural groups (IDI Resource Guide, 2021, p.30). They sense the conflict present at the lunch box moment, yet do not know how to respond appropriately.

- The Adaptation Mindset

If we want to serve our REC diverse students effectively, we need to move toward the adaptation stage, which consists of both cognitive frame-shifting (shifting one’s cultural perspective) and behavioral code-shifting (changing behavior in authentic and culturally appropriate ways). People at the adaptation stage not only value diversity, but also bridge the cultural gap by taking different cultural perspectives and proactive actions. They are true advocates for diversity and multiculturalism.

When witnessing the lunch box moment (or other discriminatory behaviors), people with an adaptation mindset may speak up for REC diverse students. They might express frustration or anger toward people who engage with diversity from other developmental orientations (IDI, 2021, p.36). Teachers with an adaptation orientation will address the biased words diverse students hear, turning the occasion into a teachable moment or even integrating it into their curriculum.

They incorporate the lunch box moment into classroom teaching because they

-

- Recognize that students’ food choices are about their cultural practices, and their lunchtime experience impacts their REC identity development;

- See the cultural assets that diverse students bring to school, from which everyone could tremendously benefit; and

- Increase a high level of parent-school collaboration.

REC diverse students will more likely feel empowered and find belonging when sharing their culture voluntarily, which will assist them to develop more positive REC identities. (Please note that examples of sharing food and culture by diverse students and their parents need to be done when the school is at the stages of acceptance and adaptation; otherwise, it could serve an adverse purpose. Sharing one’s culture needs to be a voluntary action, led by diverse students and their parents. Schools cannot ask individual diverse students to represent their entire culture group. If done improperly, it could reinforce stereotypes or confirm the misconception that culture must be exotic.)

What Can We Do as Educators?

As educators, we know we need to meet students where they are so that we can provide the right scaffolding for them. This is the same for intercultural development. To facilitate intercultural development, we can look again at the lunch box moment and reflect on our own responses. I’d offer the following suggestions as a starting point.

- Seek an In-Depth Understanding of Deep Culture

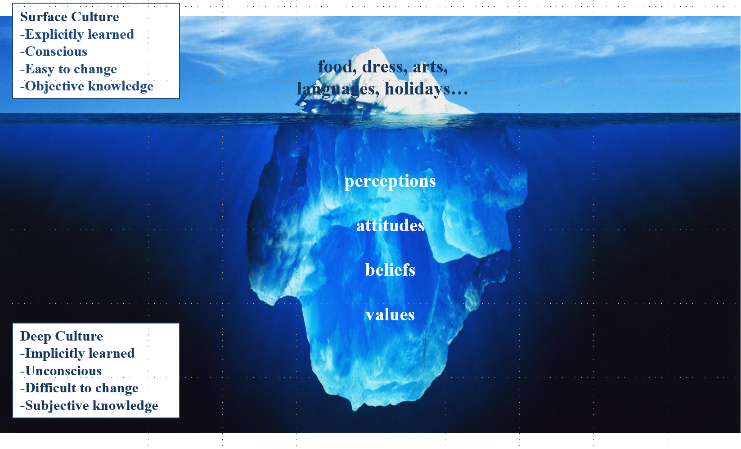

If you’re a teacher who thinks, “It’s just food. Let’s not make a big deal of it,” I’d suggest you try to notice and engage cultural differences. Seek an in-depth understanding of deep culture through surface culture. Edward T. Hall’s Cultural Iceberg Model will be a good start. First, understand that food differences are examples of surface culture; then understand that food differences are also part of deep culture underneath the sea level. They represent different cultural values and beliefs.

If you’re a teacher who thinks, “It’s just food. Let’s not make a big deal of it,” I’d suggest you try to notice and engage cultural differences. Seek an in-depth understanding of deep culture through surface culture. Edward T. Hall’s Cultural Iceberg Model will be a good start. First, understand that food differences are examples of surface culture; then understand that food differences are also part of deep culture underneath the sea level. They represent different cultural values and beliefs.

Discussions of different lunch choices are great conversation starters for topics such as culture, family, love, diversity, and values. Participate in conversations with REC diverse students during lunchtime if possible. If you’re looking for formal discussion on the topic of the lunch box moment in a classroom setting, consider the lesson plan Min Jee’s Lunch. Inspired by the questions from Min Jee’s Lunch, you could also use The Invisible Boy in your class for younger children.

- Reject Cultural Cloning

If you’re a teacher who thinks, “I need to help REC diverse students adapt to American food,” I’d suggest a slightly different way of thinking. We want to help our students “look more like Christ, not more like us” (Elmer, p.75). We must reject cultural cloning. When we approach cultural differences in terms of “us versus them,” the first step is to suspend judgment from our own cultural lens. It is essential to remind ourselves that every culture has positive and negative aspects. The Describe, Interpret, Verify, Evaluate (D.I.V.E.) method is an effective strategy when encountering unfamiliar or ambiguous intercultural circumstances:

-

- Describe: What do I observe?

- Interpret: What do I think about what is going on?

- Verify: Talk about what you see with a person who is from that culture or who knows that culture well.

- Evaluate: How do I feel positively/negatively about what I think is going on? Why do I have these positive or negative emotions?

- Learn Culture-General Frameworks

If you’re a teacher with a minimization orientation who thinks, “It doesn’t matter what we eat. People are people, and food is food,” I’d suggest that you learn culture-general frameworks to help you bridge across diverse communities. The lunch box moment could be a great study case to increase your cultural understanding about yourself and others. You might also ask diverse students and their parents about their culture. To avoid stereotyping a certain cultural group, it’s good to learn directly from people of that culture. I’d also suggest these excellent resources for learning culture-general frameworks: L. Robert Kohl’s The Values Americans Live By, The Hofstede Model of National Culture, and Mitch Hammer’s Intercultural Conflict Styles.

- Continue Deepening Your Understanding

If you’re a teacher with an acceptance orientation, you already have a positive attitude toward cultural diversity. But acceptance in the intercultural learning context does not mean approval. Romans 5:8 illustrates God’s acceptance of us despite our imperfections: “While we were still sinners, Christ died for us.” Your task is to continue deepening your understanding of culture-general and culture-specific frameworks mentioned above so that you can move toward the next developmental orientation: adaptation.

- Be a Cultural Mediator

If you’re a teacher with an adaptation mindset, you may be bicultural and are therefore capable of acting as a “cultural mediator” between diverse groups. During his mission trips, Paul took the perspectives of diverse groups (Jews, Greeks, and Romans) and adapted his behaviors in different cultural contexts (Philippians 3:4–6, Acts 22:25-29, Philippians 3:20–21, Acts 17:22-23) so that he could share the message of Christ with people of other cultures. Paul is truly exemplary:

Though I am free and belong to no one, I have made myself a slave to everyone, to win as many as possible. To the Jews I became like a Jew, to win the Jews. To those under the law I became like one under the law (though I myself am not under the law), so as to win those under the law. To those not having the law I became like one not having the law (though I am not free from God’s law but am under Christ’s law), so as to win those not having the law. To the weak I became weak, to win the weak. I have become all things to all people so that by all possible means I might save some. I do all this for the sake of the gospel, that I may share in its blessings (1 Corinthians 9:19-23).

If you’re at the adaptation stage, you may be frustrated when interacting with people from other stages. Hence, your task is to understand that other people might not have the rich cultural experiences you do and therefore may not be as adaptive as you are. You will need to be patient to work with people at the denial, polarization, minimization, and acceptance mindsets.

In Summary

Christian teachers like us who follow the Great Commission want to serve culturally diverse students and share the gospel with them. However, the action of serving is culturally dependent. As Duane Elmer, the author of Cross-Cultural Servanthood: Serving the World in Christlike Humility, shares: “Servanthood is culturally defined—that is, serving must be sensitive to the cultural landscape while remaining true to the Scripture” (Elmer, 2006, p. 12).

When serving students who are culturally different from us, we want to teach in a student-centered manner, which means teaching from students’ cultural contexts. Good intentions are insufficient when interacting with people from another culture. We need to be equipped with the knowledge and competencies to function skillfully (Elmer, 2006).

Professor Tinging Schwartz (MLC ’15) serves as professor of history/social science and secondary education and as international coordinator of the Cultural Engagement Center at Martin Luther College-New Ulm MN.

References

Banks, J. A. (1993). Multicultural education: development, dimensions, and challenges. Phi Delta Kappan, Vol. 75, pp. 22-28. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/20405019.pdf

Bailey, K. E. (2011). Paul through Mediterranean eyes: Cultural studies in 1 Corinthians. IVP Academic.

Elmer, D. (2006). Cross-cultural servanthood: Serving the world in Christlike humility. IVP Books.

Hall, E. T. (1989). Beyond culture. Anchor Books.

Harvey, T. (2017). The #1 thing you can do to help students navigate cultural differences. https://www.truenorthintercultural.com/blog/the-1-thing-you-can-do-to-help-students-navigate-cultural-differences

Karrebæk, M. (2012). “What’s in your lunch box today?”: Health, respectability, and ethnicity in the primary classroom. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology, Vol. 22, pp. 1-22.

Kohls, L. R. (1984). The values Americans live by. https://www.fordham.edu/download/downloads/id/3193/values_americans_live_by.pdf

Salazar, M. (2007). Public schools, private foods: Mexicano memories of culture and conflict in American school cafeterias. Food and foodways: Explorations in the history and culture of human nourishment, Vol. 15, pp. 153-181. https://doi.org/10.1080/07409710701620078

The intercultural development inventory (IDI) Resource guide. (2021).

IDI Qualifying Seminar Exemplars. (2021).

Great article to read. It can be hard to get to that adaptation stage, though I think there are a few great options individuals have to start growing in cultural understanding (I’m just thinking of personal experience here, so maybe there are more). First of all people can travel to different places and really take time to connect with people who live in the area versus just going to touristy areas. But travel may not always be feasible.

Connecting with people from other cultures can help us grow. I’ve recently been connecting with a refugee through an English class and listen to her tell me about what it was like for her growing up. She tells me about the food she eats and how she prepares it and so on. So listening is a great way to grow!

Then another thing we can easily do from anywhere today is learning a language, especially from a different language group from our own. Languages aren’t simply just different words for other things, but it a difference in the way people think and view the world so going past the basics of another language and really getting into an intermediate level at least lets us begin to think about those major differences in thinking and so much of culture is tied into language as well.

Looking forward to reading the next parts!