This blog ends a three-article series on the importance of adopting a culturally responsive approach in Lutheran schools. As communities become more diverse, Lutheran schools will want to become more diverse as well. Crossing cultural lines with the gospel can be difficult, as the early church quickly learned (Acts 15). The series is written by Professor Tingting Schwartz, who has personally experienced and intellectually examined these challenges, providing valuable insights to anyone wishing to minister to new people groups.

- What’s in Your Student’s Lunch Box? Focusing on intercultural competence for educators.

- What Language Do the Parents of Your Student Speak? Discussing anti-bias education for young children.

- What Books Are on Your Classroom Bookshelf? Underscoring the importance of the Racial/Cultural Identity Development (R/CID) model for racially, ethnically, culturally (REC) diverse students.

What Books Are on Your Classroom Bookshelf?

Written by Professor Tingting Schwartz

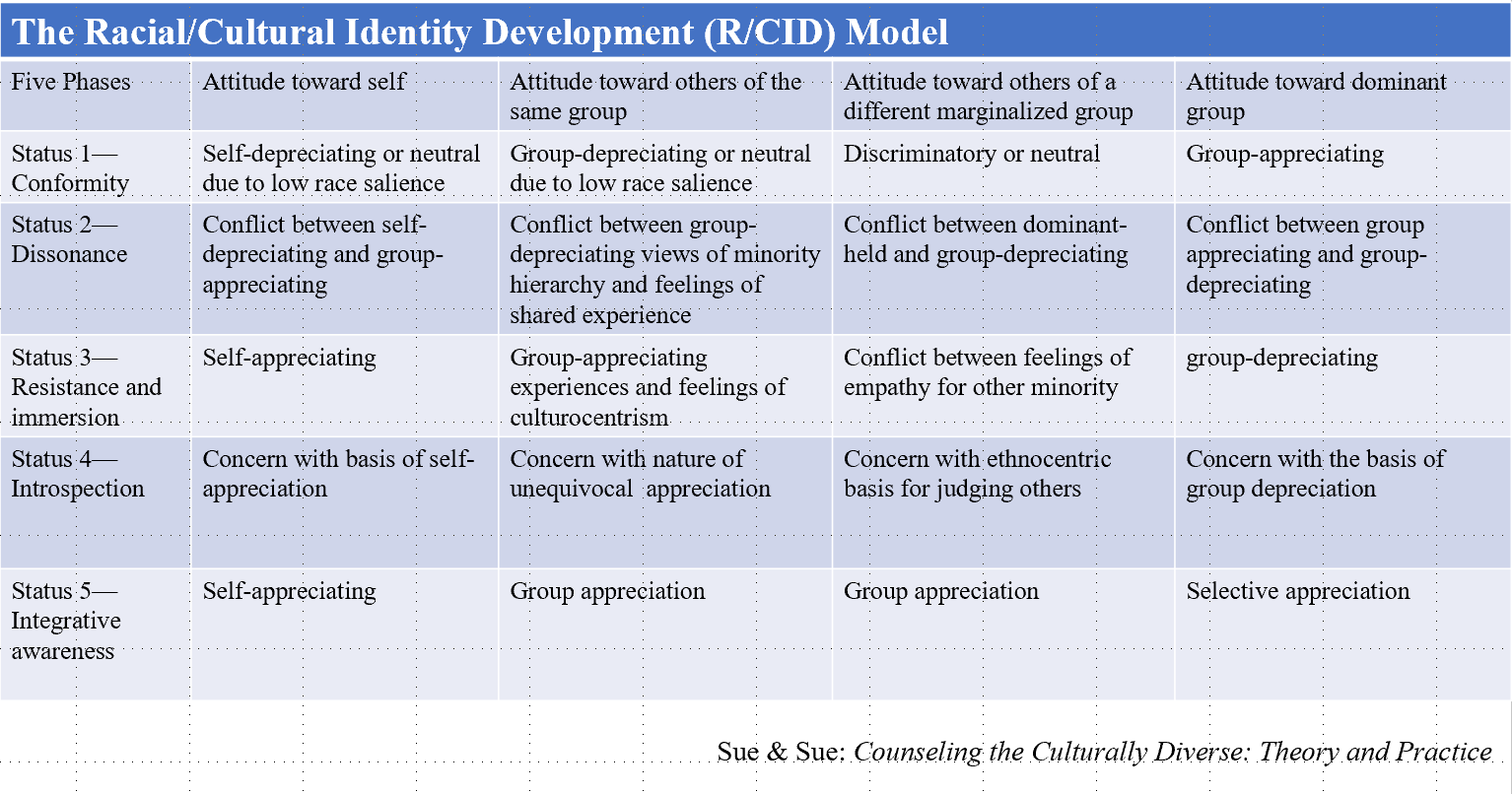

My previous blogs discussed intercultural competence development for educators and anti-bias education for young children. For the third one, using the Racial/Cultural Identity Development (R/CID) model proposed by Derald Wing Sue and David Sue, I will shift the perspective to racially, ethnically, and culturally (REC) diverse students and focus on the nurturance of their racial and cultural identity.

What Do We See?

The demographics of the United States are increasingly diversified. According to the U.S. Census Bureau (2020), the non-Hispanic white population decreased to 57.8%. The second-largest racial or ethnic group is the Hispanic or Latino population, comprising 18.7%. The third-largest group is the Black or African American population at 12.1%. The percentage of non-Hispanic white children under 18 is 49.8%, less than half of the total children population. About two in three children are projected to be a race other than non-Hispanic White by 2060 (The U.S. Census Bureau, p.8).

To reach out to a more multicultural student population, here is a question for our Lutheran teachers: “What books are on your classroom bookshelf?” I am asking this question because Rudine Sims Bishop (2015), a scholar of multicultural children’s literature, suggested books are mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors for readers:

Books are sometimes windows, offering views of worlds that may be real or imagined, familiar or strange. These windows are also sliding glass doors, and readers have only to walk through imagination to become part of whatever world has been created or recreated by the author. When lighting conditions are just right, however, a window can also be a mirror. Literature transforms human experience and reflects it back to us, and in that reflection, we can see our own lives and experiences as part of the larger human experience. Reading, then, becomes a means of self-affirmation, and readers often seek their mirrors in books.

The books on your classroom bookshelf could be a window through which your students see the lives of others they have never encountered, a sliding door that invites students to enter and engage with a different world, or a mirror reflecting their own images. However, what if your students rarely have a chance to see their images in the books they read? Or even worse, what if they only see the inaccurate, distorted images of themselves in these books?

That was Grace Lin’s childhood experience at school. As an Asian American children’s writer, illustrator, and advocate for multicultural children’s literature, Lin shared a Tedx Talk titled The Windows and Mirrors of Your Child’s Bookshelf to underscore the importance of multicultural literature to her personal journey of cultural identity development. Her talk also offered a glimpse of experiences of culturally diverse students who live and learn in a monocultural community that lacks support for them.

Please watch Grace Lin’s The Windows and Mirrors of Your Child’s Bookshelf. Her story will serve as an example to comprehend the R/CID model. I will highlight Grace Lin’s attitudes and behaviors in her talk to understand the R/CID model.

How Do We Understand the R/CID Model?

Proposed by Derald Wing Sue, professor of counseling psychology at Columbia University, and David Sue, professor emeritus of psychology at Western Washington University (2019, pp. 238-252), the Racial/Cultural Identity Development (R/CID) model is a conceptual framework for counselors and educators to understand the attitudes and behaviors of REC diverse clients and students. According to the R/CID model, REC diverse people may experience five phases of understanding their own identities—conformity, dissonance, resistance and immersion, introspection, and integrative awareness. At each level, four corresponding beliefs and attitudes are an integral part of identity: how a person views the self, others of the same minority, others of another minority, and majority individuals (or the dominant group).

Status 1—Conformity

At the initial phase, REC diverse students have a positive attitude toward the dominant cultural values since they want to be—or already are—acculturated by the dominant American culture. They often hold negative views of their own group’s physical and cultural characteristics. Low self-esteem is usually displayed in students’ attitudes.

In Grace Lin’s TEDx Talk, she shared that she did not like being the only Asian child, along with her sister, in her community. Hence, she pretended she was not an Asian by refusing to learn Chinese, but only eating McDonald’s and curling her hair. The drawing books she made only featured white characters.

Can you identify your REC students who hold conformity status? Maybe it is an African American student who has told you that she dislikes her skin color or hair texture. Perhaps it is your bilingual kindergartener who suddenly stops using his home language at home. Maybe it is your international student who insists that you call her by her English name. I had an Asian international student tell me he hated his “slanted-shaped” eyes, foreign accent, and introverted personality when he first came to the U.S. He thought his face was too flat. He wished he could have spoken the “perfect” American accented English. He pretended to be an extrovert, which is considered a sign of strong leadership in the U.S.

Status 2—Dissonance

No matter how hard students attempt to deny their REC identity and pass to the preferred social group, they may experience dissonance between the society and their own identity development.

Grace Lin shared the dissonant experiences from her childhood. While trying hard to hide her Asian identity, she was reminded in class, “Chinese? Just like you!” She felt horrified by “the reflection” of her own image in the mirror, which is one of the functions of books proposed by Bishop. However, the reflection of Chinese people from the children’s book The Five Chinese Brothers is inaccurate or even distorted compared to the images of Chinese people today. She also felt “stupid, embarrassed, and like nobody” when her classmate told her that she could not be Dorothy, a character from Return to Oz, since she is an Asian, because “Dorothy is not Chinese.” Later, she encountered a more significant dissonance when having a conversation with an Italian during her study in Italy because she could converse in Italian but could not speak one word of her parents’ mother tongue; because she was knowledgeable about Italian art and history but knew nothing about her parents’ immigration story. She was ashamed of the ignorance of her Chinese heritage, whereas, in her previous identity phase, she was ashamed of associating with Chinese heritage.

Can you identify your REC students who have experienced the dissonance between self-deprecating and group-appreciating? Maybe it is your Asian student who was proud of being a member of “the model minority.” Suddenly, she encounters discrimination personally—she is yelled at as “a human calculator” on the street. Maybe it is a Latino student who was scolded for and ashamed of speaking Spanish at an “English Only” school, and hence devalued his cultural upbringing; now he meets a white high school teacher who highly appreciates the beauty of Spanish poetry and the warmth of Hispanic culture.

Denial of their own cultural identity begins to shatter, and questions about the dominant cultural values start to rise. REC students might have mixed feelings of shame and pride about their cultural heritage. While noticing the positive aspects of their heritage culture, they also discover the negative aspects of the dominant culture.

Status 3—Resistance and Immersion

As the name of the third status suggests, REC people display resistance to the dominant values of society and immerse themselves into their cultural heritage. Their attitude toward their own REC group and the dominant group is reversed.

Grace Lin called her immersion in Chinese culture an “epiphany” because she started embracing her Chinese heritage. She began to appreciate Chinese art and adopt Chinese folk art elements, such as bright colors and patterns in her artwork. Her children’s books featured Chinese culture and Asian characters. To name a few, the children’s books that she created during this stage of her life were The Ugly Vegetables (1999), The Seven Chinese Sisters (2003), Where the Mountain Meets the Moon (2009), Thanking the Moon (2010), Bringing in the New Year (2013), and Dim sum for Everyone (2014). The Seven Chinese Sisters, illustrated by Grace Lin, a person within an Asian cultural group, contrasts The Five Chinese Brothers created by a person outside of that cultural group and criticized today for promoting ethnic stereotypes. Where the Mountain Meets the Moon, young adult fantasy literature inspired by Chinese folklore, received a 2010 Newbery Honor and was translated into many languages.

Sue and Sue (2019) marked:

The individual with this status is oriented toward self-discovery of his or her own history and culture. There is an active seeking out of information and artifacts that enhance the person’s sense of identity and worth. Cultural and racial characteristics that once elicited feelings of shame and disgust become symbols of pride and honor. (p. 243)

Do you see an REC diverse student in your classroom who embraces their cultural heritage after a long time of denial? Maybe it is an African American saying, “Black is beautiful. Black lives matter.” Perhaps it is a group of Native American students proud to share their rich and diverse traditions and languages with other students during the Native American Heritage Month in November. Maybe it is that same Latino student who refused to learn and speak Spanish for years; now he decides to take Spanish classes in college and learn more about his parents’ cultural roots.

Individuals with resistance and immersion status often possess feelings of shame and guilt because they perceive their past actions as betrayals to their cultural group. Sue and Sue also highlighted their distrust and anger toward the dominant cultural group. They tend to withdraw from the dominant culture, perceive the dominant group as an oppressor and enemies, and even instigate the destruction of the institutions and structures that represent the dominant group (pp. 243-244). As an example, we saw riots, destruction of federal monuments, and hostility toward police after the death of George Floyd.

Status 4—Introspection

REC individuals often move away from resistance and immersion when they realize the unhealthiness of projecting anger toward the dominant group. Instead of blaming the dominant group for all the problems, they begin to understand that they could spend more time and energy on their own cultural heritage. They may start to question or resent their own people’s attitudes of resistance and immersion, such as “How Black are you?” “If you support Affirmative Action, you are not Asian.” They recognize that many elements in the dominant culture are highly functional and desirable yet feel confused about how to incorporate these elements into their own culture (Sue & Sue, p. 245).

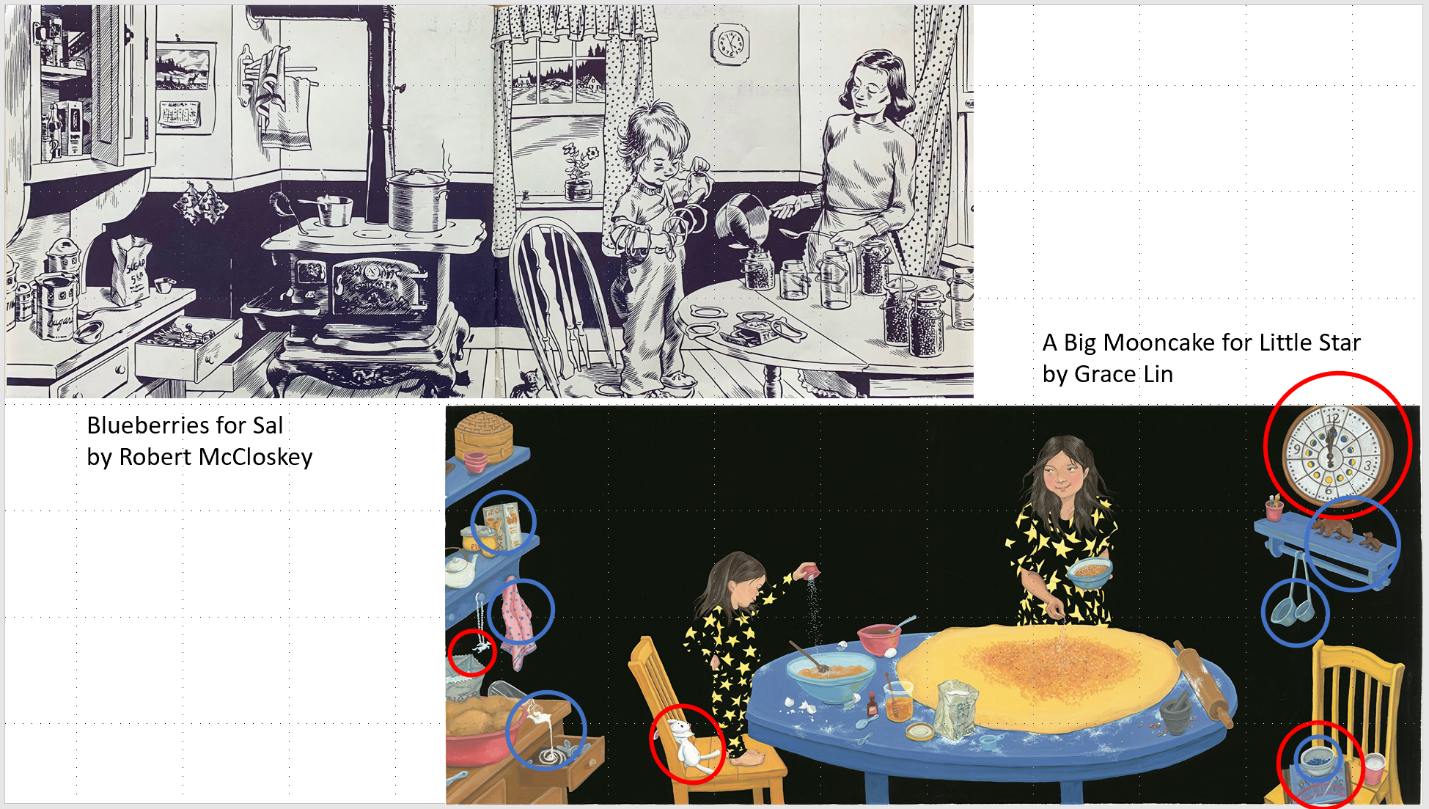

Grace Lin’s introspection is highlighted in this interview titled Book Chat with the Illustrator: Grace Lin on a Big Mooncake for Little Star. She shared her experience of seeing Robert McCloskey’s exhibition with her 4-year-old daughter at the Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art. The show’s title was “Americana on Parade,” yet she realized that there was nobody in that art that resembled them. She felt that she and her daughter were excluded from the Americana of which she wanted to be a part. She also admired the artwork of Coles Phillips, especially his book All-American Girl; but once again, she noticed these beautiful “all-American” girls were white. Her introspection began: “When you are a racial minority, who gets to decide if you are American enough? Who gets to be that all-American girl? Will my Asian American daughter be considered all-American?”

Status 5— Integrative Awareness

The examination of her own racial and cultural identity pushed Lin into the final stage of the R/CID model— integrative awareness. People with integrative awareness have developed a positive self-image and experienced a strong sense of self-worth and confidence, have become bicultural/multicultural without a sense of having “sold out my integrity,” and actively seek positive changes in the community and society. They are also aware that each group member has different identity status, and they hold no judgments. They show trust to the dominant group members who actively advocate for justice and equity (Sue & Sue, pp. 245-246).

When reading Lin’s Caldecott-Honor awarded book A Big Mooncake for Little Star (2018), my bilingual and bicultural sons and I no longer found Chinese folk-art elements. Instead, we found ourselves on a journey of discovering a fusion of Chinese and American cultures and languages. The whole story celebrates one of the most important Chinese festivals—the Mid-Autumn Festival and its moon phases. Readers familiar with Chinese culture and language will notice a bunny lovey that reminds them of the Jade Rabbit from the Mid-Autumn legend. They will find a clock with moon phases marking time in ancient China and a pendant of the Pegasus constellation called flying horse in Chinese. The Pleiades (a.k.a. Seven Sisters constellation in Chinese) is referred to as the Seven Chinese sister book under a bowl of blueberries at the bottom right corner. English readers could easily find the spilled milk resembling the Milky Way, flour bags with Orion (Hunter) constellation and Leo (lion) constellation, the Big and Little Dipper, and the Great Bear and Little Bear constellation.

In her interview, Book Chat with the Illustrator: Grace Lin on a Big Mooncake for Little Star, she shared that she designed endpapers with the color of blue, a bowl of blueberries, and a blueberry-patterned kitchen towel to pay homage to McClosky’s Blueberries for Sal. Like McClosky using his daughter in this classic American children’s book, Lin used her daughter as the center of endpapers. She captured “the same mother-daughter bond, that timeless love of family, that passing along of traditions and skills. Those things that go beyond race or nationality.” Lin created a new multicultural “Americana” by claiming both her Chinese heritage ownership and American birthright.

Have you encountered REC diverse students with integrative awareness? These diverse students often show greater appreciation and flexibility to different cultures. Teachers often find these REC diverse students go beyond their cultural groups and are actively involved with international festivals, global citizen programs, cross-cultural committees, mission trips, MLK day, etc. They show their understanding of the Great Commission by breaking down cultural barriers, learning different cultural values, and sharing the gospel with people of different cultures.

Sonia Nieto, in her book Affirming Diversity: The Sociopolitical Context of Multicultural Education (2000), summarized the successful models of REC diverse students who refused to accept either assimilation or rejection of the dominant culture:

- They have held onto their culture, or at least parts of it, sometimes obstinately so.

- They are often bilingual, even demanding to use their language in school whether or not they are in a bilingual program.

- They are involved with their peers from a variety of backgrounds.

What Can We Do as Educators?

Although we do not want to fall victim to stereotyping REC diverse students in using the (R/CID) model, just like other conceptual frameworks, it could aid us in working with them. Hence, I have three questions for you:

- Can you identify some of the REC diverse students you have worked with and their R/CID status?

- Examine your school or church’s culture. What practices might reinforce students’ conformity status and dissonance status?

- Examine your school or church’s culture. What can be done to nurture their healthy racial and cultural identity, possibly helping them reach integrative awareness status?

The following section will address the third question from the perspective of culturally and linguistically sustaining teaching pedagogy in multicultural education. Recognizing a change in the paradigm for teaching REC diverse students, I will first share how educators need to shift their belief system and then propose specific practices that validate and sustain REC diverse students’ language and culture.

Supported by research, the paradigm shift from a deficit-based mindset to an asset-based mindset toward REC diverse students seeks to support REC diverse students both culturally and linguistically. This change means educators focus on what learners can do instead of what learners cannot do. With a deficit-based mindset, educators view cultural differences as deficits and see language learners as deficient communicators striving to reach the level of an idealized native speaker because they tend to use monolingual standards to measure bilingual or multilingual learners (Firth & Wagner, 2007).

With an asset-based mindset, educators view cultural differences as assets and celebrate bilingual or multilingual learners’ success in using their linguistic repertoire (all of the linguistic varieties, including registers, dialects, styles, and accents) at communication. Educators with an asset-based mindset recognize learners creatively managing their cultural and linguistic resources rather than struggling to find a strategy to compensate for a gap in knowledge (Shrum & Glisan, 2016).

As Lutheran educators, we should ask ourselves: How often do we see ourselves as a savior to save our students (deficit-based mindset) instead of seeing ourselves as the ambassadors of our true Savior Jesus? How often do we see them as God’s loved children (asset-based mindset) instead of an object with a problem that needs to be fixed (deficit-based mindset)?

From the cultural perspective, educators with an asset-based mindset . . .

- Diversify classroom literature and other teaching tools;

- Bring multiple perspectives into learning content;

- Foster students’ positive cultural identity by pronouncing their names correctly, including students’ home language in the classroom, and highlighting their cultural strengths;

- Share cultural authenticity; and

- Adopt classroom practices that reflect students’ cultural values.

From the linguistic perspective, educators with an asset-based mindset promote additive bilingualism over subtractive bilingualism by . . .

- Affirming students when they succeed at communication by using every competency and strategy they have at their disposal (languages and dialects, language registers, discourse patterns, cross-communication styles, etc.)

- Validating students’ code-switching in a situationally appropriate way (students should not be scolded, shamed, or punished for using their native language, for instance, during recession time), and

- Adopting translanguaging pedagogy, which encourages students to expand their academic language repertoires in their native language.

Nieto (2000) highlighted the importance of cultural and linguistic identity to students’ learning. A positive and enduring sense of cultural heritage—as manifested in strong ties to the ethnic culture and maintenance of native language—is positively related to mental health, social wellbeing, and educational achievement. Selective acculturation, where learning U.S. mainstream ways is combined with sustaining strong cultural bonds, can lead to positive outcomes for many REC diverse students (pp. 289-290).

Professor Tinging Schwartz (MLC ’15) serves as professor of history/social science and secondary education and as international coordinator of the Cultural Engagement Center at Martin Luther College-New Ulm MN.

References

Association for Library Service to Children. (2014, April). The importance of diversity in library programs and material collections for children. Naidoo, J. M. https://www.ala.org/alsc/sites/ala.org.alsc/files/content/ALSCwhitepaper_importance%20of%20diversity_with%20graphics_FINAL.pdf

Bishop, R. S. (2015, March). Mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors. https://scenicregional.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Mirrors-Windows-and-Sliding-Glass-Doors.pdf

Chavez, A. F. & Longerbeam, S. D. (2016). Teaching across cultural strengths: A guide to balancing integrated and individuated cultural frameworks in college teaching. Stylus Publishing, Virginia.

Garcia, O. (2008). Bilingual education in the 21st century: A global perspective. Wiley.

Hollie, S. (2017). Culturally and linguistically responsive teaching and learning – Classroom practices for student success, Grades K-12. (2nd ed.). Shell Education.

Lin, G. (2017). The windows and mirrors of your child’s bookshelf [Video]. TEDx Talks.

(2018). A big mooncake for little star. Little, Brown Books for Young Readers.

(2019). Book chat with the illustrator: Grace Lin on a big mooncake for little star [Video]. Vimeo. https://vimeo.com/283726917?fbclid=IwAR1mrYY-miM6DI61L9bi66DkxAHP8PCAYtJ1qE8hCa2sEQWr0E71fgBWbgM

Nieto, S. (2000). Affirming diversity: The sociopolitical context of multicultural education. (3rd ed.). Longman, New York.

(2002). Language, culture, and teaching: Critical perspectives for a new century. (1st ed.). Routledge, London.

Paris. D. & Alim, H. S. (Ed.). (2017). Culturally sustaining pedagogies: Teaching and learning for justice in a Changing World. Teachers College Press.

Renkly, S. & Bertolini, K. (2018). Shifting the paradigm from deficit oriented schools to asset based models: Why leaders need to promote an asset orientation in our schools. Empowering Research for Educators. Vol. 2 (Issue 1). https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1012&context=ere

Shrum, J. L. & Glisan, E. W. (2016). Teacher’s Handbook: Contextualized Language Instruction. (5th ed.). Cengage Learning.

Sorum, E. A. (1999). Change: Mission and ministry across cultures. WELS Outreach Recourses.

Sue, D., Sue, D., & Neville, H., Smith L. (2019). Counseling the culturally diverse: theory and practice. (8th ed.). Wiley.

TESOL International Association. (2014, March). Changes in the expertise of ESL professionals: Knowledge and action in an era of new standards. Appendix: Historical and current conceptualizations of language and SLA in language teaching: A basis for rethinking, pp. 38-39. Valdés, G., Kibler, A. & Walqui, A. https://www.tesol.org/docs/default-source/papers-and-briefs/professional-paper-26-march-2014.pdf

The U.S. Census Bureau. (2020, February). Demographic turning points for the United States: Population projections for 2020 to 2060. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2020/demo/p25-1144.pdf

These are certainly difficult waters to tread. Racism is not a God pleasing thing.

At the same time, these Critical Social Justice concepts present us with serious concerns and need to be thoroughly evaluated using precise language. Unless this is done, we will not be able to properly assess and recognize the very serious dangers that these concepts introduce.

When we make use of the cultural/ideological solutions that the world produces, we find that these solutions come with their own set of risks and hazards which need to be critically examined and openly discussed. We also risk finding out that some of these solutions will make these problems more contentious.

The Critical Social Justice claims of Truth offered by our postmodern world are certainly appealing to our hearts because they appear to be founded upon Christian principles (e.g., helping your neighbor). Instead, however, we discover that those Christian principles are often turned on their head.

For example…

In Part 2, the blog offers suggestions on how to respond to microaggressions. Microaggressions, by definition, often disregard the intentions of the speaker and rely solely on the subjective perception of the listener. How might such disregarding of intentions result in a listener making slanderous accusations against a speaker?

In Part 2, the blog recommends two texts for teachers to help them implement anti-bias early childhood programs. There, we find that one of the goals of anti-bias education is to teach others to recognize “fairness”. However, when fairness lacks objective criteria, it often decays into the pursuit of envy and victimhood. What precautions do the 1st, 7th, 8th, 9th, and 10th commandments give us when teaching others to pursue an anti-bias goal of “fairness”?

In Part 3, the blog presents the Racial/Cultural Identity Development (R/CID) framework. The authors of this framework make the assumption that these are the five stages that oppressed people go through as they live in a privileged dominant culture which systemically oppresses them. This oppressor/oppressed distinction is defined, not by a person’s character, beliefs, or actions, but instead by their group identity. We then must ask ourselves, might such an assumption result in sowing the seeds of slander, covetousness, distrust, division, and hatred between those who have been classified as “oppressed” and those who have been deemed to be “oppressors” regardless of who they are as individuals?

Patrick Winkler

East Troy, WI

Nov. 2, 2022

Prof. Tingting Schwartz,

What a challenging time it is to prepare future pastors and teachers for preaching and teaching to all nations. Your three recent blog posts (How to Serve REC Diverse Students) in Issues in Lutheran Education ( https://blogs.mlc-wels.edu/wels-educator/ ) prompted some questions and I’m hoping that you will be able to clarify these for me.

1. In Part 2 of your blog, you make suggestions on how to respond to microaggressions.

Since microaggressions often disregard the intentions of the speaker and rely solely on the subjective perception of the hearer (Anti-Bias Education, Louise Derman-Sparks, 2020, p. 12; Counseling the Culturally Diverse, Sue & Sue, 2019, p. 125), …

· How might such a concept, if adopted widely, negatively affect discourse in society or even contribute to increased mistrust and conflict in society?

· Might this disregarding of intentions be considered prejudicial and discriminatory?

· How does the 8th commandment speak to such a disregarding of the intentions of a speaker?

· Might an individual, when confronted with the Law of God’s Word, perceive such as a microaggression?

You also relate an experience that you had with the 4- or 5-year-old boy in a library who characterized his own language as “normal”. It appeared from your presentation that you found his choice of words hurtful.

· Would you characterize that boy’s word choice (i.e., “normal”) as a microaggression?

· Considering the vocabulary limitations of a 4- or 5-year-old, is it possible that his word choice (i.e., “normal”) should rather have been construed as something neutral and not hurtful?

· What if, instead of a “normal-abnormal” dichotomy along with its negative connotations, this little boy was really intending to relate something neutral, such as “familiar-unfamiliar”, “familial-foreign”, or “common-uncommon” but lacked the vocabulary to do so?

· If so, how might that have affected your perception of what he said?

2. In Part 3 of your blog, you speak of the “dominant group” and “dominant culture”.

· Do you define these terms only as the majority of a populace, or, as Derman-Sparks writes, “the term does not necessarily or always mean the culture of the majority. Rather, it is the culture of the people who hold social, geopolitical, and economic power in a society”? (Anti-Bias Education, p. 57)

· If this latter definition, what are the metrics by which such a “dominant culture” is determined?

· Is the dominant culture (that is, the culture with power) the only culture that “provide[s] the environment for developing prejudice”? (Roots and Wings, p39) Namely, is power and prejudice inextricably linked?

3. In Part 3 of your blog, you present the Racial/Cultural Identity Development (R/CID) framework proposed by Sue & Sue (8th ed, 2019). The authors assume that these are the five stages “that oppressed people experience as they struggle to understand themselves in terms of their own culture, the dominant culture and the oppressive relationship between the two.” (p 238) You also mention, in Part 2 of your blog, that young “children begin to be aware of [these] power dynamics linked to social identities.”

· Would you say that this oppressed-dominant (oppressed-oppressor; Sue & Sue, p 251) dynamic constitutes the primary social dynamic between various (racial, gender, ethnic) groups in society?

· What other dynamics might be in effect when looking at the interrelationships between peoples?

· Where does the development of a White racial identity (Sue & Sue, chapter 12) fit in with the implementation of their R/CID model?

· Would you say that Sue & Sue’s R/CID model should also be used to develop Whiteness identity as the authors suggest? (Sue & Sue, p 263f)

4. Much of your blog has talked about the biases people/students have and how those biases can affect dealing with REC (Racial, Ethnic, Cultural) issues. At the same time, we should also recognize that the authors of the R/CID framework (Sue & Sue) have their own set of biases and assumptions which drive their sociological models. Examples of some of these are as follows…

a. “Racism is an integral part of U.S. life, and it permeates into ALL ASPECTS of our culture and institutions. Know that as a White person, you are not immune.” (Sue & Sue, p 273) (emphasis mine)

b. “Whites are socialized into U.S. society, and therefore inherit ALL its biases, stereotypes, and racist attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors.” (Sue & Sue, p 263) (emphasis mine)

c. “The status of White racial identity development in any multicultural encounter affects the process and outcome of interracial relationships.” (Sue & Sue, p 264)

d. “The most desirable outcome is one in which the White person not only accepts his or her Whiteness but also defines it in a nonracist and antiracist manner.” (Sue & Sue, p 264)

e. Whiteness is associated with unearned privilege (i.e., White privilege) and involves “having the power to define reality.” (Sue & Sue, p 258)

f. White racism toward people of color is so ubiquitous and insidious that many/most people are not able to discern that it exists or what it looks like. White people need assistance to discern that such racism exists everywhere in society. White people need to develop a White nonracist/antiracist “racial awakening” and “commitment to social action” (i.e., activism). “Dealing with racism means a personal commitment to action.” (Sue & Sue, p 259, 261-262, 268, 272-273).

· Could you comment about whether you agree with these biases and assumptions?

· Might these assumptions about racism foster increased distrust and paranoia between races?

· How might variations in the character of individuals affect these assumptions?

· How might these assumptions affect the content of Sue & Sue’s R/CID model?

5. In Part 2 of your blog, you encourage teachers, as they start anti-bias early childhood programs in their respective schools, to “seek more information through these two resource books” (i.e., Anti-Bias Education, Derman-Sparks, 2010; Roots and Wings by York, 2016). You recommend these books without qualification or exception. Would it be helpful to offer some qualifications/exceptions/limitations for your recommendation of the Louise Derman-Sparks text due to …

· Negatively characterizing a group of people based primarily on the color of their skin, for example, “White children definitely need anti-bias education. So, too, do children of color, although the specific work differs from that with White children.” (p. 7).

· The authors’ discussions about implementing an anti-bias curriculum with respect to Religious Diversity (p. 70-71), Gender Diversity (ch 7) and Family Structures (ch 9)?

· The text’s causal attribution that “children of color are still disproportionately living in poverty” is solely due to racism (Derman-Sparks, p 77) and an “inequitable society” (Derman-Sparks, p. 3) rather than including other factors such as the effect of fatherless homes.

· The authors’ vision of anti-bias work is to create a world in which “all children and families … experience affirmation of their identities…” (p. 2)

6. In presenting anti-bias principles, the authors (Derman-Sparks, Edwards) often speak of the concept of “fairness”. In the first few pages, they note…

Equity: Treatment that is fair and just… (p. xii)

ABE Goal 3: Each child will increasingly recognize unfairness (p. xiv)

…build children’s budding capacities for … fairness (p. 5)

… pave the way for their learning to take action to make unfair things fair (p. 5)

· How might the criterion of “fairness” be tied to an objective standard?

· How might such an appeal to “fairness” be made without resorting to a pursuit of envy and victimhood?

7. Where does social justice activism, as recommended by Louise Derman-Sparks (p 28), fit with your recommendations for anti-bias programs in education?

Thank you for your time. I look forward to hearing your thoughts.

Patrick Winkler

East Troy, WI